My exploration of geospatial mapping analysis through GIS left me with some profound questions about the nature of our experiences and their context chronologically and spatially. Chief among my interests was the exact nature of James Merrill Linn’s emotional state as his narrative progressed through the Battle of South Mills. While not particularly dense in technical specifics, my transcription excerpt was rich in emotional detail. In this survey I will attempt to characterize Linn’s emotional state through a spatial context. The question is simple; how did where Linn was, effect what he felt? More specifically, how do geography, distance and battle positions effect Linn’s emotions as expressed in his diary? Are there turning points and climaxes in respect to time and place? The first step was to analyze Linn’s text by sentence and assign a “sentiment score” on a scale from 5 to -5. This score is a qualitative judgment of the mood expressed by a sentence. For example, “I was exhausted, I felt like I would die.” receives a score of -5 as most negative number corresponds to the most negative sentiment. The sentence, “They came out in a wonderful order and we raised our colors high.” is an example of a very positive sentence with a score of positive 5. In the between 1 and -1 is 0, or neutral, where no descendable sentiment is expressed. I experimented with digital methods for sentiment analysis using python and online software but most of these programs were qualitatively wildly inaccurate, or inconsistent. This was the goal originally to remove any artifacts of editorializing or personal prejudices from the analysis but the software proved to be entirely ineffective, a manual qualitative analysis was sufficient for shorter pieces of text.

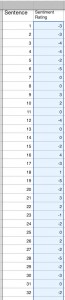

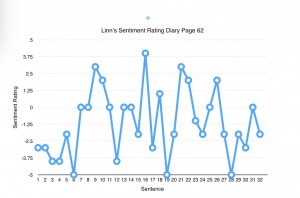

Figure 1 shows the sentiment for each of the 32 sentences the transcription contained. The sentiment score is put into a table next to its respective sentence allowing for the generation of a line graph illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2 was the first visualization created in this investigation and it reveals the relationship of time and Linn’s emotions. Because of the linear relationship of sentences in his narrative, this graph reveals the chronological progression of Linn’s text. In the graph itself, the line at zero indicates a neutral emotion and peaks positive in the y-axis indicate a favorable emotion while negative in the y-axis is a unfavorable emotion.

Using Linn’s text, sentiment analysis and outside resources such as period and modern maps and battle descriptions, a detailed and multilayered world can be built. In her article, Graphephesis, Drucker discusses the various forms information can be represented and visualization schemes through history. Drucker mentions that certain data representations such as the grid coordinate system inherent to line graphs and maps drawn with respect to coordinates have only existed within the last three centuries. Drucker explains that there is a rich millennia-old history surrounding information representation systems, including maps based on landmarks, locations placed in terms of relationships and calendars based on star positions and concentric circles. Similarly, this investigation will create a map based on emotion, where objects of influence, movement and the passage of time can all come together to form a picture of the feelings behind an experience.

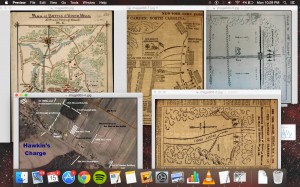

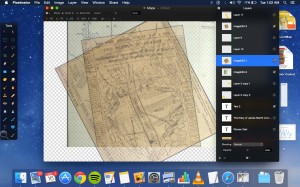

The process involved in creating such a map includes several outside sources of information. Maps of civil war battles often were not laid out in terms of accurate locations on a coordinate grid, but the relative positions of troops and objects in the form of simple illustrations. these maps were overlapped and a composite map based on most likely relative position was formed. Figure 5 shows the progress of this aggregate map. While they do not perfectly line up, the positions of cannons, batteries and troop positions relative to fences and the road can be established. An overlay consisting of vector shapes was necessary to anchor the positions. Every road, river and canal’s position was extrapolated from several period maps and overlaid on the aggregate. Later, troop positions and movements of Linn’s regiment are overlaid from the path that Linn describes and the path confirmed from other sources. Dots representing Linn’s position with respect to each sentence are placed on top of the path. A color gradient was devised with bright red representing -5 and bright green for 5)

With the finished pictorial diagrams, map and line graph it is immediately possible to see certain trends and turning points within Linn’s narrative. From this context-rich model of Linn’s world for that day, we can see objects and forces which affected his emotions. For example, the long walk from Elizabeth city ends near South Mills. It is clear through Linn’s writing that this journey was arduous and some of his most negative sentiments come from right before battle when Linn is exhausted from walking. Almost the entire beginning of his path is highly negative until he begins battle. The positions of his comrades next to him and their performance have a noticeable effect on his sentiment (the 9th of New York in particular).

One very curious trend that I noticed was that the language Linn uses to describe events changes from when he is marching to when is fighting. Linn used the word say, “Here I was so

completely exhausted that I begged Col Bell to give me Lt Beaver as I could not proceed” and “I thought would die” to and express his deeply agitated state just walking from Elizabeth city. When his men start dying in front of him and the enemy is in sight is language changes very subtly near sentence 17. Near the end of the diary he writes, “ fell and was unconscious for a little while – but recovered & staggered on, supported by some of my men. I am yet unable to say whether it was a faint or something struck me. I can’t find any mark the rebels left. But once we were unable to pursue, being too much exhausted.” While his state is similar, presumably he is more exhausted, he does not use the impassioned voice when recalling these events.sub He recounts his fallen men impassively, his own injuries in the heat of battle are described as a physician would describe them, a general emotional separation. While a more thorough analysis would be necessary, I hypothesize that Battle changes Linn’s emotional state -as evident in the language he uses when recalling it- so that an psychological armor is put in place to hide him from the horrors he was witnessing. Today we know of several psychological conditions and disorders that affect veterans of modern wars. During Linn’s time psychological services were non-existent. Through analysis of writings from Civil War veterans it is known that disorders like PTSD, brain injuries and emotional trauma were rampant among the many diseases during the American Civil War (Ford).

Citations

Linn, James Merrill. Diary. April 19th, 1862. MS. Bucknell University Archives and Special Collections, Lewisburg, PA.

Drucker, Johanna. Graphesis: “Interpreting Visualization::Visualizing Interpretation.” Visual Forms of Knowledge Production. Harvard UP, Cambridge, MA

Ford, Sarah M. “Suffering in Silence:.” Psychological Disorders and Soldiers in the American Civil War. Kutztown University, n.d. Web. 15 Dec. 2014.

The Battle of Camden. Digital image. Battle of South Mills. New York Herald, n.d. Web. Published May 4th, 1862

The Battle of Camden. Digital image. Battle of South Mills. New York Tribune, n.d. Web. 6 May 1862

The Battle of Camden. Digital image. Battle of South Mills. New York Times, n.d. Web. Published on May 8th, 1862