In this blog I will show how people from all over the world can come together to help dissect the manuscripts of Jeremy Bentham. Bentham, a renowned Anglo-American philosopher, was one of the most influential people of his era, which is why people are still trying to completely understand his work.

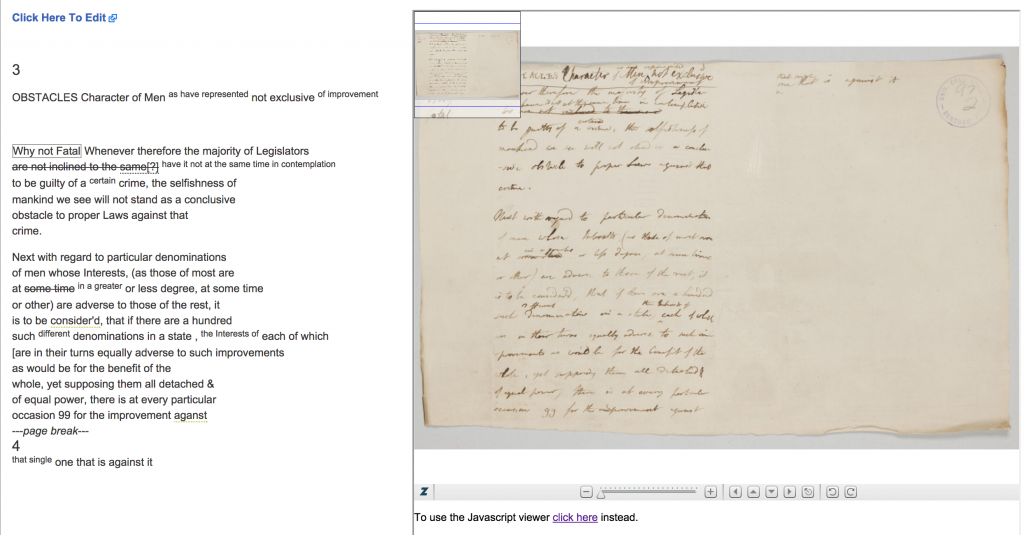

The primary DH focus of this site is to transcribe Bentham’s work with teamwork. As Bentham once said, “Many hands make light work. Many hands together make merry work.” Through things such as the Transcription Desk, historians from allover the world are able to dig through Bentham’s 26,796 manuscripts.

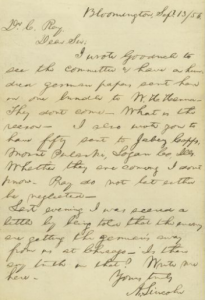

The Transcription Desk is the major initiative to deciphering Bentham’s manuscripts. With the archives coming from the University of College London and the funding from AHRC, anyone can join to see if they are able to transcribe. The manuscripts are also split up into Easy, Moderate and Hard. With this, transcribers can decide which difficulty fits them the most so they don’t become lost in Bentham’s many manuscripts.

Because Bentham is one of the most famous philosophers of all time, it is vital to come together as a single community to complete the never-ending journey of deciphering his manuscripts. These manuscripts vary in topic everywhere from capital punishment to sexual morality. With people from all over and so many different topics, anyone can choose a particular topic that interests them. If they are interested in science they won’t be forced to transcribe a manuscript about the arts. This is just another benefit of having a worldwide place to transcribe.

This project allows us to become better versed in Bentham’s work and to learn things that we may have never discovered if we were transcribing by ourselves. Ideas are brought together, people can discuss and our society can progress as a whole.