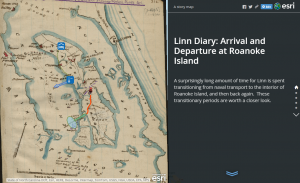

GIS, Geographic Information System, helped us visualize the life of James Merrill Linn and the Civil War by showing us the travel path he took. Throughout the class, we have been introduced to different techniques which people have used to decode a text and learned to derive information through various means: TEI, TimeMapper, Voyant Tools, Transcribing. This tool is the most effective so far. It allows us to see many layers of information letting us to obtain a lot more informations. We are able to see it in geographic form and displaying informations including time and context.

Bodenhamer says “We recognize our representations of space as value-laden guides to the world as we perceive it” (14). We often associate ourselves with where we are from and where we have been. Locations has always been an important of our lives. Being able to see Linn’s experience in terms of location and path, we are able to integrate more information than we could with other kind of representations. With the help of GIS, we can display the location, time, and context of these events.

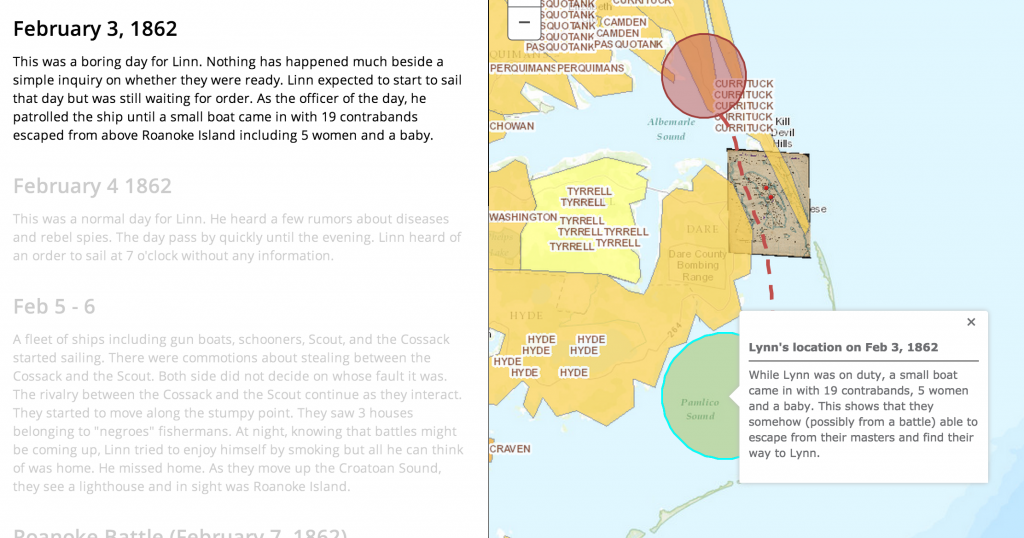

In my experience with GIS, using a layer for the concentration of slaves in the United States in the 1860s and the battle won by the North, I was able to estimate the location for the 19 contrabands’ origin. In the diary, Linn says “a small boat came in, said to have had on board 19 contrabands, who escaped from above Roanoke — 5 women & a baby”. From seeing the concentration of battles won by the North close to Roanoke, we are able to see its correlation with the escape of the slave.

“Evidence about the world depends on the perspective of the observer” (19). In the diary, Linn mentioned that the gun boats went between Tyrrell Shore and Roanoke Island. As we can clearly see, Tyrrell is the slave concentration area which is far from Roanoke Island. Without the help of GIS, we would not have question Linn’s directional sense. This ,however, can also means that the maps they had back then was not accurate. The answer to this is not important but what important is the question itself. Without GIS, we would never have come up with this hypothesis and therefore another piece of information.

“Evidence about the world depends on the perspective of the observer” (19). In the diary, Linn mentioned that the gun boats went between Tyrrell Shore and Roanoke Island. As we can clearly see, Tyrrell is the slave concentration area which is far from Roanoke Island. Without the help of GIS, we would not have question Linn’s directional sense. This ,however, can also means that the maps they had back then was not accurate. The answer to this is not important but what important is the question itself. Without GIS, we would never have come up with this hypothesis and therefore another piece of information.

Bodenhamer says “visualize a spatially accurate physical and manmade environment that proved the attraction” (21). We were able to walk in Linn’s shoes. He noticed sightsee, he observed the shore and the lighthouse, He had a smoke at night. Seeing how close he was to the battle, we can have a close reading on his personal life.

Link to Map: http://bit.ly/1t6CIED