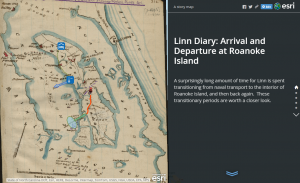

My research question for this project was whether or not James Merrill Linn had a major impact on the Battle of Roanoke Island, or if he just seemed important because of his concise account. To discover the answer to this question, I wanted to compare the movements of Linn to the overall movements of the Union and Confederacy. If Linn happened to be in an important position during a turning point of the battle, he would be considered to have a major impact. I first read all of Linn’s diary entries from February 7th to the 12th, 1862. These entries gave me a picture of the Union’s as well as Linn’s positioning during these dates.

Luckily, these entries had already been transcribed, so it was easy for me to decipher what Linn was saying. Without prior transcription, this process would have been very tedious and time consuming.

Next, I then used ArcGIS to map out the positioning of Linn and the Union, as well as the Confederates. This process was much more difficult because the maps from 1862 are not exact replications of what the land actually looked like. Men who had walked the island drew these maps from hand; therefore, there was slight error when looking at exact positioning of troops.

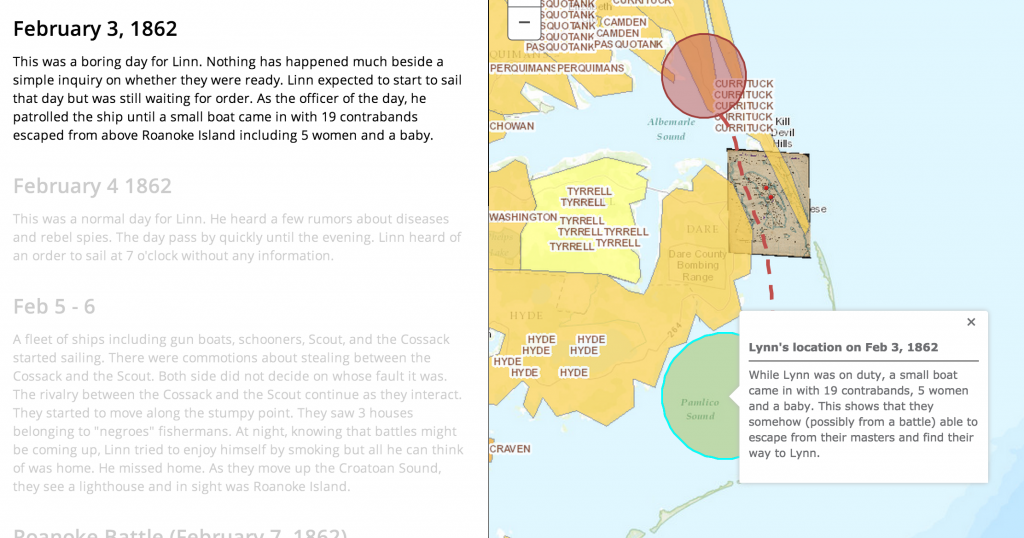

To illustrate the different movements of Linn, the Union and the Confederacy, I gave each subject a color. Linn was represented by purple, the Union by blue and the Confederacy by red. This helped show just from a glance at the map that was moving where.

On the positive note however, these maps did provide a unique look into what the soldiers were seeing in 1862. This is very evident in the layer “Roanoke1862” because the locations of the ships, forts and guns were drawn onto the map. This especially helped the mapping process because it gave me the locations of different Union soldiers that Linn left out in his diary. For example, in the map below, you can see exactly where the Rebels surrendered. In Linn’s diary, he fails to mention the location of where the Rebels actually surrendered, just the location of himself when he heard the news.

Upon completion of the map, I was able to see where Linn’s regiment was located during the actual land battle. This gave me good insight on his regiment’s importance to the battle, and whether or not they achieved any heroic actions. The 51st Pennsylvania (Linn’s Regiment) was located right along side the Rhode Islanders, in the bottom right corner of the Union’s positioning. This was very far away from the Confederate’s battery (as you can see in the map below). Looking closely, one can see that the Pennsylvania and Rhode Island regiments are in fact very close to each other.

This is vital because Linn points out that much of the Pennsylvania regiment ends up getting intertwined with the Rhode Islanders. Though not intentionally, this is somewhat comical because while the battle rages on up ahead of them, Linn is worrying about which of his men became tangled up with the Rhode Islanders. This in turn supports my hypothesis of Linn not being very vital to the overall battle, he just happened to have a very detailed account.

It was through the completion of this map that I discovered that all fighting had stopped on February 8th. This was surprising at first because Linn’s diary account of Roanoke Island lasts until the 12th. Upon further inspection, I was able to conclude that after the battle, Linn in fact traveled all over Roanoke Island. Whether he was completing menial tasks for the military, or just relaxing on the shore, Linn paints a picture of what he accomplished after the battle. Due to the fact that he was simply completing menial tasks, I at first did not find his travel on the island important. After looking intently into his positioning however, I realized that Linn was able to see the island in an entirely different way from the Confederates. Being the victor, allows one to really see the beauty of the land he is fighting on. While the Confederates were being shipped to prisoner of war camps, Linn was able to take in just how beautiful Roanoke Island is. He realizes this when sitting on the shore with Jim, George and Gibson, watching prisoners being transported to the ships.

In conclusion, ArcGIS is a fantastic tool to map out the Battle of Roanoke Island, while at the same time, look at the significance of Linn in the battle. I was able to see that while the battle was raging at the Confederate battery, Linn was in fact far behind, trying to assemble lost troops. Also, Linn was not in fact present when the remainder of the Confederate troops surrendered. He was notified by General Foster, who on horseback, ran into Linn and his regiment on their way back from the battery towards headquarters. Both of these examples solidify my hypothesis of Linn not having a major impact on the overall battle. We are assuming he had one because of his very in depth diary.

In order to see my web application click here: http://bit.ly/1wKZsy0

Citations

Linn, James Merrill. Diary. [February 7-12] 1862. MS. Bucknell University Archives and Special Collections, Lewisburg, PA.

“Map of the Battlefield of Roanoke Id. Feb. 8th 1862 / | Library of Congress.” Map of the Battlefield of Roanoke Id. Feb. 8th 1862 / | Library of Congress. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Dec. 2014. <http://www.loc.gov/item/99447476/>.

“Map of Roanoke Island. [February 8, 1862]. | Library of Congress.” Map of Roanoke Island. [February 8, 1862]. | Library of Congress. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Dec. 2014. <http://www.loc.gov/item/99447479/>.

“Evidence about the world depends on the perspective of the observer” (19). In the diary, Linn mentioned that the gun boats went between Tyrrell Shore and Roanoke Island. As we can clearly see, Tyrrell is the slave concentration area which is far from Roanoke Island. Without the help of GIS, we would not have question Linn’s directional sense. This ,however, can also means that the maps they had back then was not accurate. The answer to this is not important but what important is the question itself. Without GIS, we would never have come up with this hypothesis and therefore another piece of information.

“Evidence about the world depends on the perspective of the observer” (19). In the diary, Linn mentioned that the gun boats went between Tyrrell Shore and Roanoke Island. As we can clearly see, Tyrrell is the slave concentration area which is far from Roanoke Island. Without the help of GIS, we would not have question Linn’s directional sense. This ,however, can also means that the maps they had back then was not accurate. The answer to this is not important but what important is the question itself. Without GIS, we would never have come up with this hypothesis and therefore another piece of information.