The Movement of General Burnside’s Armada

http://bit.ly/1vWDVP6

When I started this project, I knew I wanted to talk about Linn’s naval travel, but I was unsure about what specific aspect would be most interesting. My research question was how did naval warfare effect the way that the Civil War was fought, and how did the weather, tides, wind, and other nautical issues effect the way that the war played out. The answer, however, was hidden deeper than I expected. In order to start teasing out the answers to those questions, I began to read through both the Linn diary from January 6th to February 1st and the 3rd and 4th chapters of the Burnside Diary, highlighting things that were related to naval movement, a struggle that they faced while on the water, and anything that I thought could be added to my map to further my story. Both accounts go into incredible detail about the terrible struggles they faced while on these ships, and my fear changed from not knowing what to talk about to not knowing how to pick out the best information and represent it on my map. My next issue was going to be finding what could be depicted as text and what could be added as visuals. After highlighting some sections of all of the texts, I went back through and changed the color of highlighted sections to green that I thought could be represented with symbols on my map.

As I continued to do this, I complied a sort of relative timeline, which was, at its core, chronological, but at the same time was not necessarily linear. I found that although information may not be grouped together in the journals, adding it together on my map would allow better understanding of how issues related to nautical travel harassed them during their passage. After moving all of the information from the highlighted journals to the progression of the story that I wanted to tell, I found that I had both information that was clumped linearly and information that went together best when pulled from different areas and presented together.

Unable to find a true ending in the information that I had, I decided to continue on in the Burnside Biography, reading the 4th chapter, when I had initially intended to just use the 3rd, and decided that the perfect ending for my story was when they disembark from the Cossack and arrived at Roanoke. Then, I went onto my map and went through my new “storyboard,” adding map notes in places where I thought they would better represent an ideal better than just pure text. I broke these up into several different layers so that I could isolate the notes that represent different types of events, obstacles, and movements.

Then, I started to move the rest of my story into the panels, while trying to connect the images on my map to the writing on the panels. As I continued to work, my idea of how I was going to represent my story changed again, and I put different pieces of information where I thought they fit best, not necessarily where they landed in the story. After looking over what I had added and what I had left out so far, something that I found that I had not added were a lot of the direct quotes from the journal. Although I had used these quotes as evidence for some of the text in my side bar, I thought that adding the first hand perspective of these soldiers would strengthen my argument. In order to do this in a matter than continued my exploration of combining visual and textual aspects, I decided that the best place to include these quotes was in the bubbles of the map notes. By adding the quotes to these notes, I hoped to allow the reader to draw a deeper understanding of both what these visuals truly represented and how they connect to the writing in the side bar.

The quotes also proved helpful in other ways, as the combination of quotes, historical maps, and the distance indicators on the charts allowed me to estimate several locations, such as the wreckage of the Pocahontas. In the journal, Linn describes the wreckage to be 15 miles above the lighthouse, so using the distance measures on the chart I literally used a note card to measure out 15 miles and guess where the wreckage could be.

Because I had to estimate a lot of the locations, using bubbles and free form areas seemed like the best option because it allowed some error in my approximations. The intersection of visuals and text turned out to be one of the hardest aspects, as representing a complex story through multiple different outlets is never easy. As things began to come together, I looked back over what I had done to see if I thought it presented my story well. Although I do believe that there are some limitations to the ArcGIS software, I think that there was no other medium that could present my story in a better way. By integrating visuals and text, I was able to show the audience the movement of the ships, key points of interest, projected locations of different anchorages, wrecks, and lighthouses, as well as explaining the story of the armada and the struggles they faced. A perfect example of this integration is my work on the “swash,” which was represented with a combination of quotes, map notes, text in the side bar, and an additional historical chart.

Although all of this process may seem important, the building blocks of what of my successful story erupted from the storyboarding process. By laying out what I wanted to say, it allowed me to see all aspects of my thoughts, and manipulate them in the easiest way for my audience to understand. The image that my work had created said less about how naval warfare affected the Civil War as whole, but endless information on how the natural struggles of naval travel inhibited the travel and success of Burnside’s armada, and additionally, how the weather and its associates, such as wind, current, tide, waves, and fog, affected their movement and the advance of the armada as a whole. The data projected a story about nature, whether it be the land itself or the weather, and its effect on travel, and less about the war and the actual battles. The ships constantly had to stop sailing because of thick fog, lost contact with each other due to heavy winds and large waves, and in some cases, the ships were wrecked due to any number of reasons including being stuck on sand bars because of wild tides, thrown into each other by waves, and having water overflow over the sides while in the valley between waves. The Civil War was a dangerous era in naval travel, mostly because of the lack the technology we have today, and the Burnside Armada would have faced issues even in the most spectacular of weather. However, because they faced one of the worst storms in years, the struggles associated with naval travel were increased exponentially. This project allowed me to foster a deeper understanding of both naval travels during this time and how drastically weather conditions can alter the success of a voyage.

Bibliography

Foster, John G. Sketch Showing Route of the Burnside Expedition [to Roanoke Island, N.C., February 6, 1862]. Digital Image. Digital image.Library of Congress. Washington, Government Printing Office, 1866. Web. 12 Dec. 2014. <http://www.loc.gov/resource/g3901s.cw0317120/>.

Hatteras Inlet Map. Digital image. Sons of the South. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Dec. 2014. <http://www.sonofthesouth.net/leefoundation/civil-war/1862/february/hatteras-inlet-map.htm>. I found this map inside of a Harper’s Weekly Civil War newspaper from February 15th, 1862.

Linn, James Merrill. Diary. January 6th– February 1st 1862. MS. Bucknell University Archives and Special Collections, Lewisburg, PA.

Major-General Ambrose E. Burnside and the Ninth Army Corps: A Narrative of Campaigns in North Carolina, Maryland, Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, Mississippi and Tennessee, During the War for the Preservation of the Republic. Chapters 3-4. Augustus Woodbury, 1866

“Map of the North Carolina Coast.” Extract from Harper’s History of the Great Rebellion, Feb. 1862, p. 243. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/ncmaps/id/887/rec/26

United States Coast Survey. Preliminary Chart of Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina. Digital image. Library of Congress. N.p., 1862. Web. 12 Dec. 2014 <http://www.loc.gov/resource/g3902h.cw0316700/>.

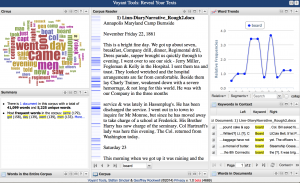

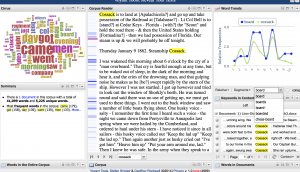

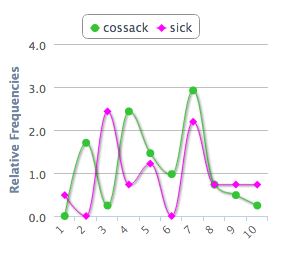

e another. The first thing I noticed was how extreme the frequencies were, they never really remained flat for a long period of time. The result of comparing them was also not what I expected. In segments 1, 2, 3, and 4 the two words did not have even slightly similar word trends, they were complete opposites. However, in segments 5, 7, 8 and 9 they had either identical word trends or very similar ones, as shown below. And although this somewhat supports my hypothesis, it does not completely.

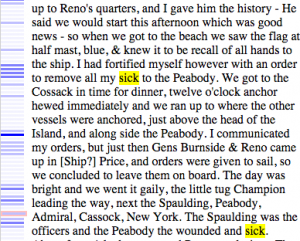

e another. The first thing I noticed was how extreme the frequencies were, they never really remained flat for a long period of time. The result of comparing them was also not what I expected. In segments 1, 2, 3, and 4 the two words did not have even slightly similar word trends, they were complete opposites. However, in segments 5, 7, 8 and 9 they had either identical word trends or very similar ones, as shown below. And although this somewhat supports my hypothesis, it does not completely. diary entry, “sick” was used 4 times, and in the one right after it was used 5 times. “Cossack” is used, as I expected, most often when they are aboard the ship, but also when they are about to go on it or right after they got off the boat. The word frequencies overlap especially in segments 5 and 8 because that is when the men in the army and their prisoners were getting very sick aboard the ship.

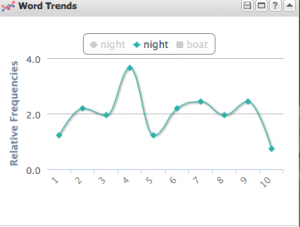

diary entry, “sick” was used 4 times, and in the one right after it was used 5 times. “Cossack” is used, as I expected, most often when they are aboard the ship, but also when they are about to go on it or right after they got off the boat. The word frequencies overlap especially in segments 5 and 8 because that is when the men in the army and their prisoners were getting very sick aboard the ship. The first world I selected was “night.” This word appears 82 times throughout the text. As I clicked on the word in cirrus tool and viewed it on the word trends tool, I did not notice any patterns whatsoever. Especially during the time period Dr. J. addresses, there was a consistent frequency of the number of times night was used. It also did not appear to be too much different than the beginning diary transcripts, either. Distant reading using this word alone, did not help with Professor Jackacki’s research question.

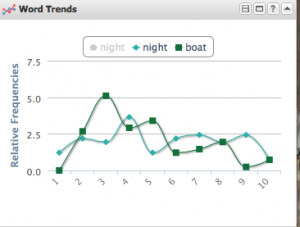

The first world I selected was “night.” This word appears 82 times throughout the text. As I clicked on the word in cirrus tool and viewed it on the word trends tool, I did not notice any patterns whatsoever. Especially during the time period Dr. J. addresses, there was a consistent frequency of the number of times night was used. It also did not appear to be too much different than the beginning diary transcripts, either. Distant reading using this word alone, did not help with Professor Jackacki’s research question. However, when I added a second word, “boat,” I noticed a distinct interesting. I noticed these two trends were almost mirror images of each other. There seemed to be a negative correlation between talking about night and talking about boats. Whenever Linn was talking about a boat, typically the Cossack, he did not seem to be mentioning night. This leads me to the question: when Linn is on board the Cossack, is he writing at night, therefore he does not mention night, or does all the action seem to talk place during daylight hours? Why does is there this strange relationship between “boat” and “night”?

However, when I added a second word, “boat,” I noticed a distinct interesting. I noticed these two trends were almost mirror images of each other. There seemed to be a negative correlation between talking about night and talking about boats. Whenever Linn was talking about a boat, typically the Cossack, he did not seem to be mentioning night. This leads me to the question: when Linn is on board the Cossack, is he writing at night, therefore he does not mention night, or does all the action seem to talk place during daylight hours? Why does is there this strange relationship between “boat” and “night”?